Uploading Rage: The DIY Birth of a Viral Katrina Remix

In the chaotic days after Hurricane Katrina (landfall: August 29, 2005), I made a remix video sparked by Kanye West’s live remark on September 2, 2005. This is the behind‑the‑scenes of how it came together—gear, grit, politics, and all the messy human feelings.

FRANK'S BRAIN

Franklin López

8/28/20256 min read

Opening Scene (Hook)

Around this time, 20 years ago, I was in Atlanta, Georgia. That’s not particularly weird since I used to live there, but the road that led me back was. Earlier that May, I had moved to Vancouver, BC, chasing a new chapter. A couple months later, an arsonist set our building on fire, and I lost everything. Me and my partner packed up what little we had left and headed back to Atlanta to pick up some work from old clients and save enough to rebuild our lives in Vancouver. Thankfully, I walked out of the fire with my laptop and my trusty Canon GL2 Mini‑DV camcorder, so I could still make videos.

And then word got out that Hurricane Katrina had hit New Orleans. For those who don’t know, Katrina was a devastating storm that reached Category 5 intensity in the Gulf and made landfall as a Category 3, bringing brutal winds, torrential rain, and catastrophic flooding. The levees that were supposed to protect neighborhoods like the Ninth Ward—a historically Black and poor part of the city—failed, and the water swallowed entire blocks. Back then the president was George W. Bush, and the response from his administration was slow, to say the least. The city was drowning, people were dying, and the White House’s handling became a symbol of detachment—remember the Aug. 29 McCain birthday photo op and the Aug. 31 Air Force One flyover—while people on the ground were pleading for help.

By then, I had developed an extreme disliking of George Bush, to put it mildly. Not only was he a conservative asshole, but he also unleashed the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, where the death toll reached into the millions—all under the false pretext that Saddam Hussein and the Taliban were somehow linked. It was a war built on lies, a shameless grab for oil, and it radicalized me even further.

And as somebody who had spent a lot of years in the South, I had a deep love for New Orleans. I visited often, and it always felt like a city apart from the rest of the U.S.—a place where cultures collided in the best way possible. The food, the music, the architecture—it’s picturesque, rooted, and alive. Sure, everyone knows about Mardi Gras, but there’s also the Jazz Fest, the Treme neighborhood, second line parades, and that intangible magic you can’t replicate anywhere else. If you want to understand why New Orleans is so special, check out the TV series Treme, or dive into Harry Shearer’s podcast and radio show Le Show. That city deserves to be cherished—not abandoned to drown.

People all across the United States were furious at how slow and callous the federal response had been. Many pointed out that if the disaster had struck New York City or some rich enclave, the cavalry would’ve arrived immediately. But in New Orleans, it was mostly poor Black people stranded on rooftops, and they were left to suffer.

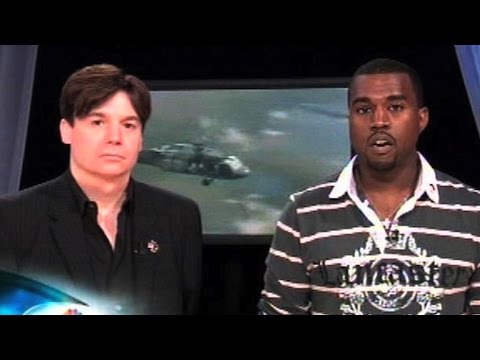

In the middle of this outrage, a bunch of celebrities got together for a televised fundraiser. At one point, it was Mike Myers and Kanye West’s turn to speak. Myers stuck to the script, but Kanye went rogue. He looked into the camera and dropped the infamous line: “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people.” A few years ago, Bush confessed that he was livid at Kanye for that.

That moment exploded. It was raw, unscripted truth broadcast live, and it reverberated across the country. It also hit at a time when Kanye had just released his single Gold Digger, which sampled Ray Charles. Not long after, a Houston rap crew called The Legendary K.O. (also known as K‑Otix)—released under a Creative Commons license picked up the beat and freestyled over it, turning Kanye’s line into a full track: George Bush Don’t Like Black People.

That song would become the backbone of the remix video I was about to make.

Edit Sprint: 24 Hours of Fury

I went straight to work. I started hunting for images and TV clips that matched the lyrics bar‑for‑bar. In under 24 hours, I cut a video with the same name—George Bush Don’t Like Black People—and gave it a black‑and‑white, film‑damage treatment to make the whole thing feel like a scratched‑up historical document.

For titles, I used intercards styled after D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation—a deliberate Easter egg. That film is infamous: a racist epic that mythologized the KKK. Echoing its typography and silent‑era cadence was my way of saying: we still live in a racist nation that doesn’t care about Black people.

To juice the energy, I built a motion filter that pulsed subtle zoom‑ins and zoom‑outs on the beat and bassline. The rhythm wasn’t just in the music—it lived in the cuts and the forward creep of the frame.

When it was ready, I exported a QuickTime file and uploaded it to the Internet Archive—one of the only places then where you could host video and embed it on your own site. YouTube had just launched that year; I hadn’t even heard of it yet. I posted the embed on subMedia.

Distribution: Stone‑Age Virality (2005‑style)

“Viral” then meant word of mouth and email chains. I blasted it to my list; people forwarded it; forums picked it up. Soon, The New York Times ran a piece about the track “George Bush Don’t Like Black People” and linked to subMedia, which crashed the site. The video also landed on iFilm, which actually showed view counts—there it cleared 100,000+ views in a couple of days. That was my oh‑shit moment: this kind of remix could channel anger and still travel.

It’s worth stressing how not‑easy sourcing was. Without the DVR/TiVo setup, I would’ve had to sit through live TV and try to tape segments as they aired. There was no ripping clean clips from YouTube—that ease came later. Back then, only a handful of us were doing this consistently. And we stood on shoulders: crews like Emergency Broadcast Network (EBN) were chopping CNN in the early ’90s—think George H. W. Bush “singing” “We Will Rock You” as a critique of the first Gulf War. That lineage mattered to me.

Production: How the Sausage Got Made (Fast)

By this point, I already had years of remix work under my belt. When I heard George Bush Don’t Like Black People making the rounds, I knew instantly I could turn it into a music video. And remember—this was 2005. There was no SoundCloud, no Spotify, no easy way to share tracks. This song spread old‑school: people emailing MP3s to each other, posting download links on message boards, trading burned CDs. That DIY virality made it even more urgent to give the track visuals.

So I said, “Fuck this shit, I’m making a music video.”

My buddy—who I happened to be crashing with at the time—had a DVR, a TiVo. For younger folks, this was a device you hooked up to your cable TV that let you record shows and movies to watch later, instead of catching them live. I asked him to record as much Katrina coverage as possible. Once he had a bunch of news clips saved, I rigged up my Canon GL2 camcorder to the DVR’s output and used it as a bridge to capture footage onto my Apple PowerBook G4. There was no clean file transfer—this was all real‑time. I had to hit play on the DVR and manually capture the clips I wanted, one by one, into Final Cut Pro. Those raw, shaky transfers became the source material for the video that would soon go viral.

Conclusion

I didn’t set out to make a “viral” anything. I had a scorched backpack, a beat‑up PowerBook, a GL2 that still smelled like smoke, and a head full of New Orleans. The clip was a pressure valve and a loud fuck you to a government that treats poor Black people as expendable. If the piece landed, it’s because it refused neutrality. It took a line everyone felt in their bones and cut it against images no one should’ve had to see.

What I learned making this in a day is what I still believe now: speed and clarity beat polish and permission. Remix is a tactic, not a genre. You pull from the culture that raised you, you credit the people who made the sounds—shout out to Legendary K.O. / K‑Otix—and you aim every frame at power, not at the people surviving it.

Looking back, I’m proud of what a busted laptop, a TiVo, and a community of pissed‑off strangers managed to do together. The point wasn’t views. It was signal—to the peeps at Common Ground, to kids learning to edit in their bedrooms, to anyone who needed language for their rage. The work isn’t to go viral; it’s to be useful.

So if you’re reading this because you want to make something: do it. Borrow a camera. Jack the news. Cut until the beat tells the truth. Make your own damn video. And when the next disaster hits—and it will—don’t wait for permission from the people who keep failing us. Hit record.

With love and rage, for New Orleans.

Amplifier Films

Amplifying voices for revolutionary change through film.

Amplifier Films in your inbox

Your dollars keeps us rolling and our coverage independent

CONNECT